Figure 1 (click to enlarge)

THE POMPEII FORUM PROJECT1

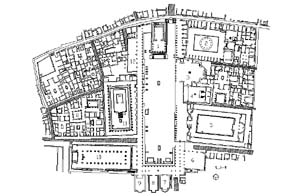

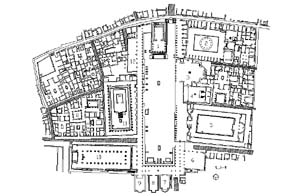

The Pompeii Forum Project was formed in 1994, after several years of independent research by its principle investigator. Our primary focus is archaeological, but the Pompeii Forum Project is also a collaborative, interdisciplinary project, using advanced technology to study the history and evolution of the forum as well as broader issues of urban development pertaining to the relationship between the forum and the areas surrounding it (Figure 1, Figure 2). Project members include archaeologists, computer specialists, architects, an urban historian, an urban designer, and a structural engineer.

|

|

Figure 1 (click to enlarge) |

Figure 2 (click

to enlarge)

|

By conducting several types of research simultaneously (archaeological, urbanistic, structural, etc.) and recording as much of our data as possible in a 3-D CAD model (for example, fig. 3), we can reconstruct not only individual buildings, but also how the whole forum evolved, explaining how the Pompeii forum arrived in its current configuration. For example, structural damage from the earthquake of A.D. 62 included several passages of out-of-plane failure in the Macellum, reconstructed (fig. 4) by our structural engineer, Kirk Martini. Three-dimensional data assembled using CAD technology assist the archaeologists in reconstructing building phases and relating them to the known history of Pompeii (fig. 5). In general the Pompeii Forum Project investigates standing remains that have not been sufficiently studied, but when research questions cannot be addressed by noninvasive means, we make small excavations devoted to answering specific questions, as in 1997 and 2001.

This paper presents only our major results.2 For more detail, scholars are invited to consult our publications and the Pompeii Forum Project website at .3 We concentrate on three critical periods in the development of the forum:(1) the period between the earthquake of A.D. 62 and the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79; (2) the Augustan period; and (3) the Sullan conquest of 89 B.C. and the foundation of the Roman colonia after 80 B.C. We begin at the end, with the post-earthquake period, and work backwards in time through the other two periods (fig. 1).

Mau, Maiuri, and many others claim that in 79 the forum was a builders' yard and that only minimal repairs had taken place. Indeed, the forum suffered greatly in the earthquake, but repairs were well advanced by 79.4 The buildings on the east side of the forum are particularly informative. Preserved evidence demonstrates that all structural repairs had been completed and a splendid decoration program had been applied throughout, including marble revetment on all building facades and throughout the Imperial Cult Building. The Imperial Cult Building itself was a new contribution to the forum after the earthquake, with its façade colonnade neatly tied in with the pre-earthquake colonnades of the surrounding buildings (fig. 5). Side streets were blocked according to the aesthetic needs of this grand new project as well. Similar reconstruction and aggrandizement were complete at the south end of the forum and a fine decoration scheme was either complete or nearly so. The whole west side was apparently rebuilt and improved to a similar state. In sum, by A.D. 79 the Pompeii Forum was nothing like a builders' yard surrounded by ruins, but was the nearly completed result of a huge project of both reconstruction and aggrandizement. This splendid recovery after the earthquake bespeaks a vibrant economy, and probably significant imperial patronage, in a city of considerable civic pride.

Previously the Augustan period had also seen considerable aggrandizement of individual buildings in the Pompeii forum, but no urbanistic project for the entire forum. Several examples are by now familiar. For instance, in the Sanctuary of Augustus (the so-called Temple of Vespasian) extensive repair and redecoration prove that the building is earlier than the earthquake, confirmed by the Augustan iconography on its altar.5 Similarly, in the Eumachia Building heavy damage and subsequent repair indicate original construction before the earthquake while the extensive allusions to Livia in the dedicatory inscription (CIL X, 810-11) and building design point to an apparently Augustan date.6

Quite surprising, however, is our Augustan date for the current form of the Sanctuary of Apollo, based on our 1997 excavations.7 Figure 1 highlights the present street system in the area of the forum while figure 6 highlights an earlier street system that has been altered and suppressed by urban developments as the aggrandized and expanding forum encroached on surrounding areas of the existing city. At the northwest corner of the sanctuary an expansion of the sacred space caused a deformation in the street pattern. This is a common urbanistic principle: the hierarchy of building types. As a sacred space, the sanctuary takes precedence over the street, and causes its deflection. In turn, the street-a public space-takes precedence over a private house, forcing the house to be truncated to make way for the deflected street. Two details compare the original condition (fig. 7) and the present condition (fig. 8): house VII.15.7 originally had a normal square corner, which was replaced by an oblique wall when the street was forced to take over that space by the expanded sanctuary.

We should emphasize the intimate chronological connection between the sanctuary's expanded wall and its tufa colonnade because our stratigraphic analysis involves only the wall, but not the colonnade directly. The most architecturally important feature of the expanded sanctuary is, of course, the colonnade. The expanded wall is simply the means by which a new space was created to accommodate the colonnade, but then it cannot be overemphasized that the colonnade is not possible without the wall. It is quite evident that the colonnade is incompatible with the earlier street system and the contemporary earlier precinct. Eventually, changes within the sanctuary rippled through the adjacent neighborhood and provide the researcher with several opportunities to investigate those changes stratigraphically.

When did these changes to the sanctuary and to the surrounding street pattern take place? The traditional answer has been the second century B.C., because the famous tufa colonnade was dated by Mau to the so-called "tufa period" of that century.8 This is not tenable, however. Both epigraphical and archaeological evidence demonstrate an Augustan date for the expanded Sanctuary of Apollo, including the tufa colonnade. The epigraphical evidence consists of an inscription from the sanctuary naming the magistrate, M. Holconius Rufus, who served in the Augustan period (CIL X, 787).9 The inscription indicates that special legal accommodations were made on behalf of the sanctuary during the Augustan period, including the modification of at least one house next to the sanctuary.10

Could the Augustan-period changes specified in the inscription be linked to the changes in the streets and houses just described? To test this hypothesis the Pompeii Forum Project placed three saggi in and around the sanctuary, looking for context material to date the walls specifically (fig. 8).11 Trench 1, in vicolo del Gallo, revealed the foundation trench of the sanctuary wall (fig. 9). The foundation trench was easy to identify and its distinctive rubble fill included fragments of terra sigillata and early imperial lamps (fig. 11), clear proof that the sanctuary wall itself is of Augustan date. Figure 10 is a section showing the foundation trench and the layers through which it cut.12 Similar fragments were found below the street pavers (fig. 12) establishing an Augustan terminus post quem for the foundation trench and confirming that the latter is indeed Augustan or later.

The same evidence comes from Trench 2 inside house VII.15.7 (fig. 8). Trench 2 exposed the foundation trench for the new oblique wall created when the displaced street cut off the original square corner of the house. That oblique house wall and the expansion of the sanctuary should be contemporary with each other, and, not surprisingly, its foundation trench had the same kinds of evidence as the foundation trench of the Sanctuary of Apollo, including terra sigillata. Our conclusion is surprising, but clearly documented: the expanded sanctuary wall, the street through which it cut and the rebuilt house wall are all parts of just one project, of Augustan date or later.

The importance of trench 2 cannot be overemphasized. It confirms the contemporaneity of the expansion of the sanctuary, the deflection of via del Gallo, and the consequent construction of the oblique house wall, and it corroborates the findings from trench 1. It also offers a formidable challenge to those who would try to salvage the second-century date for the sanctuary colonnade by arguing that the west wall is merely a local Augustan phenomenon unassociated with earlier second-century modifications in vicolo del Gallo.13 If this were the case, then we would expect second-century material from the foundation trench of the house wall, since later revisions in the sanctuary would no longer have any bearing on the house across the street. House VII.15.7 would only have been modified when the street was originally shifted, remaining independent of any later revisions in the Sanctuary of Apollo thereafter. Dating the shift of the wall in VII.15.7 therefore dates the original shift of the street, which in turn dates the original expansion of the sanctuary into this neighborhood. Given the evidence from trench 2, therefore, the Augustan material in Trench 1 cannot be interpreted as minor repairs isolated exclusively within the sanctuary. Their ramifications reached across the street in the Augustan period and that fact is crucial. Any rebuttal of our findings must address the late first-century ceramics in trench 2.

Inside the sanctuary, as argued above, the tufa colonnade could not have been built until the expanded sanctuary wall had created a space for it. The sanctuary wall is the terminus post quem for the colonnade, which, in turn, must therefore be Augustan or later too. On the other hand, our excavations prove that the east wall of the sanctuary belongs to a pre-Augustan period.14 The excavation did not date the east side absolutely, but only demonstrated that the east wall and piers were earlier than and different from the Augustan tufa colonnade inside the sanctuary. The sanctuary's east wall, however, is an integral part of a much larger project in the Pompeii forum, which we date to the Sullan period.

Finally, there is the Sullan period, from 89 to 80 B.C. This was a crucial turning point for Pompeii because in that decade the city became Roman. Not only did Sulla import a Roman population (a veterans colony), but he introduced institutions, including the Latin language, Roman weights and measures, and a Roman constitution. Similarly, the new Roman inhabitants of Pompeii added a number of new buildings of familiar Roman type, including the Forum Baths, the Amphitheater, and the Theatrum Tectum.

Given the Sullan period change in constitution and political practice, it might be expected that considerable, commensurate change would also be made in the forum area, but, strangely, the Sullan period in the forum has generally been ignored by modern scholars. The fault, once again, lies in Mau's notion of the tufa period. The grand tufa projects in the Pompeii forum are known well enough, but because of the traditional presumption that tufa construction necessarily dates to the second century B.C., scholars have generally been content to presume that there was a great group of tufa buildings, of generally Roman types, that were inexplicably built before Pompeii had any use for them, and that there was therefore no Sullan phase in the forum at all, indeed no Roman construction in the forum area until the time of Augustus or later. This is not only illogical, but also contrary to the actual archaeological evidence. Moreover, the notion of the Limestone and Tufa Periods themselves has been widely contradicted by modern archaeological study in Pompeii, including not only our own discoveries just discussed, but also the work of others.15 Finally, the idea that the very center of Pompeii was architecturally sterile during the most pivotal decade of its history is not credible. We therefore reopen the debate and re-examine the evidence for the earliest monumentalizing of the forum.

The traditional interpretation places the regularization of the Pompeii forum in the second century B.C., including the Sanctuary of Apollo, the Basilica, the Porticus of Popidius, and the Temple of Jupiter as contemporary urban elements forming the early forum. We agree that these buildings should be grouped together, and we add the Comitium to that list. On the other hand, we are still working on the Temple of Jupiter, so for now we will not offer a detailed assessment of it. We emphasize that the links among all of these buildings are so close that one can speak of an ensemble; it is an intentionally intimate grouping, conceived on an urbanistic scale. By the same token, the grouping is not simply contemporary buildings standing in the same area. We call this urbanistic project the "Popidian ensemble". It is a master plan for the whole forum area, employing tufa quadratum as its primary material. Prior to this Sullan project, no attempt had been made to regularize or aggrandize the Pompeii forum at all.

We can reconstruct the pre-Sullan forum in a general way (fig. 13). As the Comitium was carved out of the northwest corner of residential block VIII.3, we can reconstruct pre-Comitium houses there. Maiuri's excavations revealed shops in front of the Eumachia Building, behind which we posit houses. At the south end of the forum Maiuri found three non-aligned facade walls belonging to three non-domestic buildings that preceded the present civic buildings. Beneath the Basilica there were walls that suggest a non-domestic building, but not enough evidence to reconstruct its design. In the pre-Sullan period the forum was irregular in most details. Its shape was only vaguely rectangular and its axis was not precisely defined, whether or not the Temple of Jupiter existed at the time. No side was straight, and each building presented its own facade and individual orientation to the forum. The elements did not relate to each other in a design sense or to any grander overriding principle, but rather each individual building was designed according to its own specific needs, and each was oriented according to the other buildings in its own block, not according to the orientation of the forum. The only factor that linked the pre-Sullan buildings at all was proximity.

The key feature in the Sullan project is the Porticus of Popidius, which derives its name from an inscription found in front of the basilica. The inscription (CIL X, 794) reads V.POPIDIVS / EP.F.Q. / PORTICVS / FACIENDAS / COERAVIT; "Vibius Popidius, son of Epidius, Quaestor, had the colonnades made". There is only one colonnade to which this inscription can refer, the tufa colonnade at the south end of the forum. We are convinced by the analysis of Giovanni Onorato whose 1951 study dates the Popidian dedicatory inscription to a period after 89 B.C. because it is in Latin, and before 80 B.C. because the Roman colony at Pompeii did not include the office of quaestor.16 The Porticus of Popidius is the only feature of the Sullan period that is specifically dated, but fortunately it is also the most important feature of the whole group, the one component with which every other component is directly linked. So linking the other buildings to the Popidian colonnade also dates the buildings.

The role of the porticus of Popidius in shaping the forum is crucial. Its southern wing defines the south end as a straight line, while its corners and northward returns define the south corners and east and west edges of the forum. The Popidian colonnade also established the central axis of the forum, either taking that axis from the capitolium (if the temple predates the colonnade) or, perhaps more likely, establishing the axis in concert with the capitolium (if the temple too is part of the Popidian ensemble). So strong was the organizing impact of the colonnade that all subsequent buildings conform to it. That is, the buildings around the forum had to fit into the available space within their own city blocks, but now that their facades had to conform to the regularlized forum, many buildings employed a wedge-shaped element that makes the transition between the axis of the building and the axis of the forum (fig. 14). Prior to the Popidian colonnade, there would have been no purpose for such wedge-shaped porches and, not surprisingly, none were built. More important, whenever such a wedge-shaped element is an integral part of a given building on the Pompeii forum, the Popidian colonnade is a terminus post quem for that building.

The relationship between the Porticus of Popidius and the Comitium is instructive (fig. 15). In front of the Comitium the two eastern files of the porticus are irregular in informative ways: first, they have different numbers of columns (9 in the outer file, 8 in the inner), which do not align with each other. The irregular spacing of the inner portico is chronologically crucial because it responds to the pier spacing of the Comitium, especially the central opening. If the Comitium's west wall had not existed when the inner colonnade was built, the colonnade would certainly not have been arranged in this awkward manner. We would expect the same number of columns in both colonnades, lining up with each other. Instead, the east colonnade responds to the Comitium piers. The Comitium is therefore a terminus post quem for the colonnade.

Conversely, the Comitium could have occupied the entire corner of the insula from which it was carved if the colonnade had not been present (fig. 16). Instead, the colonnade cuts a substantial piece out of the earlier property lot, necessarily so because the colonnade had to establish the southeast corner of the forum in a location rigidly fixed by the main axis of symmetry and the existing southwest corner. The comitium façade was therefore displaced the east, making room for the Popidian colonnade in front of it. The colonnade therefore determines the position and orientation of the Comitium's façade, i.e., the colonnade is the terminus post quem for the Comitium. So the Comitium and the Popidian colonnade are each a terminus post quem for the other, which can only mean one thing: they are contemporary. Equally important, the Comitium was constructed using the Roman foot of .295 m. and not the Oscan foot of .275 m. Pier dimensions, individual ashlar blocks, and openings between the piers are all in Roman feet of .295 m. (fig. 17).

The Basilica, too, displays a similarly intimate relationship with the colonnade. The façade wedge is again instructive for it implies that the Basilica responded to the tufa colonnade, which either pre-existed the Basilica or was contemporary with it (fig. 14). If the Basilica had been the earlier of the two structures there would have been no need for the wedge-shaped chalcidicum. Similarly, the tufa piers of the chalcidicum confirm that the Basilica was responding to the original tufa colonnade in front of it because the Doric pilaster strips on the outer piers conform to the colonnade in motif, and height (fig. 18). More important, the basilica's façade piers are an integral structural part of the Popidian colonnade, supporting the inner ends of its joists and rafters. And finally, the Roman foot is also employed throughout the Basilica.17 The Basilica, then, is part of the Popidian ensemble too.

The Popidian ensemble extended north of the Basilica as well, as demonstrated by tufa columns in via Marina and tufa pilasters of identical form on the northeast corner of the Basilica and southeast corner of the Sanctuary of Apollo (fig. 19). Since the tufa pilasters at the southeast corner of the sanctuary, which respond to the Basilica, to the two columns in via Marina, and to the forum colonnade, are integral to the tufa piers of the east side of the sanctuary, the east side of the sanctuary is also drawn into the Popidian ensemble. Moreover, because the piers are wedge-shaped and form a special link between the disparate axes of the sanctuary and the forum, the design of the sanctuary's east precinct wall serves the same function as the wedge-shaped porches of the other buildings surrounding the forum (fig. 14). So the Sullan period is the terminus post quem for the east side of the sanctuary, while our own excavations, noted above, establish that the east side is earlier than Augustus. The Popidian ensemble, clearly, is the best likelihood for the east side of the Sanctuary of Apollo.

In sum, it appears that there was a tufa ensemble in the forum, the Popidian ensemble, all constructed under Roman oversight in the early years of the Sullan period, 89-80 BC. The buildings of this ensemble are closely linked in design and structure, as well as contemporaneous in construction. The obvious conclusion, and one that the Pompeii Forum Project offers, is that there was one grandiose project to create a regularized forum, embodied most notably by the tufa colonnade and also including the Comitium, the Basilica, the via Marina gateway, and the east wall of the Sanctuary of Apollo. The zone created by the new forum measures 500 x 110 Roman feet (fig. 14). No single, evidentiary smoking gun dates the whole, but the weight of all the evidence leads to an obvious conclusion: The Popidian ensemble is the first major urbanistic project of ROMAN Pompeii, an emphatic and unambiguous assertion of the Roman presence.

John J. Dobbins

University of Virginia

dobbins@virginia.eduLarry F. Ball

University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point

lball@uwsp.edu

1As always, we are happy to acknowledge the Soprintendenza archeologica

di Pompei, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of

Virginia, and private contributors. We especially thank Andrew Wallace-Hadrill

who read the paper at the conference in our absence. Photographs are by

J.J. Dobbins; CAD plans by K.M. Hanna and J.J. Dobbins; other credits appear

in the figure captions.

2A close study of the remains on the east side of the forum by Kurt Wallat

has produced results different from our own: "Opus Testaceum in Pompeji,"

RM 100 (1993) 353-82; Die Ostseite des Forums von Pompeji (Frankfurt am

Main 1997).3John J. Dobbins, ";The Altar in the Sanctuary of the Genius of Augustus

in the Forum at Pompeii," Romische Mitteilungen 99 (1992) 251-63;

idem., "Problems of Chronology, Decoration, and Urban Design on the

Forum at Pompeii," in American Journal of Archaeology 97 (1994) 629-94;

idem., "The Imperial Cult Building in the forum at Pompeii," in

Alastair Small, ed. Subject and Ruler: The Cult of the Ruling Power in Classical

Antiquity. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplement no. 17 (Ann Arbor 1996)

99-114; idem., "The Pompeii Forum Project, 1994-1995," in Rick

Jones and Sara E. Bon, eds. Sequence and Space in Pompeii (Oxbow Press,

Oxford 1997) 73-87; John J. Dobbins, Larry F. Ball, James G. Cooper, Stephen

L. Gavel, and Sophie Hay, "Excavations in the Sanctuary of Apollo at

Pompeii, 1997" American Journal of Archaeology 102 (1998) 739-56.4A. Mau (trans. F.W. Kelsey), Pompeii: its Life and Art (New York 1902) 94-118;

A. Maiuri, L'ultima fase edilizia di Pompei (Rome 1942) 25-30, 40, 212,

215; idem. Alla ricerca di Pompei preromana (Naples 1973) passim. See Dobbins

1994, nn. 8-9 for more recent citations.5Dobbins 1994, 661-68; Dobbins 1992.<br>

6Dobbins 1994, 647-61; L. Richardson, jr, "Concordia and Concordia Augusta:

Rome and Pompeii," PP 33 (1978) 260-72; idem. Pompeii: An Architectural

History (Baltimore 1988) 194-98; V. Kockel, "Funde unf Forschungen

in den Vesuvstädten," AA 1986, 457-58.

7Dobbins et al. 1998.

8Mau 1902, 81; H. Lauter, "Bemurkungen zur spathellenistischen

Baukunst in Mittelitalien," JdAI 94 (1979) 390-59, esp. 416-36; P.

Arthur, "Problems of the Urbanization of Pompeii," Antiquities

Journal 66 (1986) 29-44, esp. 33; Richardson, 1998, 94; P. Zanker, Pompei:

Societa, immagini urbane e forme dell'abitare (Turin 1993) 62; idem.,

Pompeii: Public and Private Life (Cambridge, MA 1998) 53, 65; E. La Rocca,

M. De Vos, and A. De Vos, Pompei (Milan 1994) 103-107.9M. Holconius Rufus d[uum] v[ir] i[uri] d[icundo] tert[ium], C. Egnatius

Postumus d. v. i. d. iter[um] ex d[ecurionum] d[ecreto] ius luminum opstruendorum

HS 00 00 00 redemerunt, parietemque privatum Col[oniae] Ven[eriae] Cor[neliae]

usque ad tegolas faciundum coerarunt. Marcus Holconius Rufus, duumvir with

judiciary authority for the third time, and Gaius Egnatius Postumus, duumvir

with judiciary authority for the second time, in accordance with a decree

of the decuriones (city council), purchased for 3,000 sestertii the right

to block light and had a private wall constructed on behalf of the colony

of Pompeii all the way to the roof tiles (trans. J.J. Dobbins).10 In addition to house VII.15.7, whose corner was modified, house VII.7.2,

just west of the sanctuary, must also have experienced changes. Windows

or even a door may have opened onto an earlier street that ran between the

house and the sanctuary. At the least, the new west wall of the sanctuary

would have reduced or eliminated the light entering into the house from

the east, a point specified in the inscription. The expanded sanctuary may

also have eliminated an earlier communication to the street.11Dobbins et al. 1998.

12Although the fill was uniform, it was removed as six separate deposits,

or "stratigraphic units," in order to provide vertical separation

of the artifacts, thereby confirming that they extended to the full depth

of the fill. Their chronological significance would be much reduced if they

were associated only with the upper few centimeters of fill.13 Zanker 1998, 79. Zanker's publication was prepared in advance of our 1998

article, but other more recent oral comments indicate that some still adhere

to a limited Augustan intervention that preserves the traditional date.14Dobbins et al. 1998, 752-56.

15 M.G. Fulford and A. Wallace-Hadrill, "Towards a history of pre-Roman

Pompeii: excavations beneath the House of Amarantus (I.9.11-12), 1995-8," Papers

of the British School at Rome 67 (1999) 37-144, esp. 37-40; idem., "Unpeeling

Pompeii," Antiquity 72 (1998) 128-45, esp. 128-29 and passim; idem.,

"The house of Amarantus at Pompeii (I, 9, 11-12): an interim report

on survey and excavations in 1995-96," Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 5

(1995-96, publ. 1998) 77-113; P. Carafa, "What was Pompeii before 200

BC? Excavations in the House of Joseph II, in the Triangular Forum and in

the House of the Wedding of Hercules," in S. E. Bon and R. Jones, eds.,

Sequence and Space in Pompeii (Oxford 1997) 13-31, esp. 20-21 for a late

date for the tufa portico in the Triangular Forum; idem., "The investigations

of the University of Rome "La Sapienza" in Regions VII and VIII:

the ancient history of Pompeii," in C. Stein and John Humphrey, eds.,

Pompeian Brothels, Pompeii's Ancient History, Mirrors and Mysteries, Art

and Nature at Oplontis, & the Herculaneum 'Basilica', Journal of Roman

Archaeology, Supplementary Series, 47 (Portsmouth 2002) 47-61, esp. 51-2

(tufa portico); S.C Nappo, "Urban transformation at Pompeii in the

late 3rd and early 2nd c. B.C.," in R. Laurence and A. Wallace-Hadrill,

Domestic Space in the Roman World: Pompeii and Beyond, Journal of Roman

Archaeology, Supplementary Series, 22 (Portsmouth 1997) 91-120, esp. 91

concerning Sarno limestone. Our own investigations in the Augustan-period

Eumachia Building argue that the original colonnade was tufa and that the

post-62 colonnade was marble: Dobbins 1994, 659-60.16 G. Onorato, "Pompei municipium e colonia romana," Rendiconti della

Accademia di Archeologia Lettere e Belle Arti, n.s. 26 (1951) 115-56.17 Karlfriedrich Ohr, Die Basilika in Pompeji (Berlin 1991) embraces the traditional

date between 150 and 100 B.C. (p. 1). Ohr posits a foot of .2935 m., a Roman

foot although he does not say so specifically, and argues against Maiuri's

assumption of an Oscan foot module (p. 34, n. 142). Ohr's measured plans

present the evidence; the Roman foot is found repeatedly throughout the

Basilica.